Miroslav Krejsa

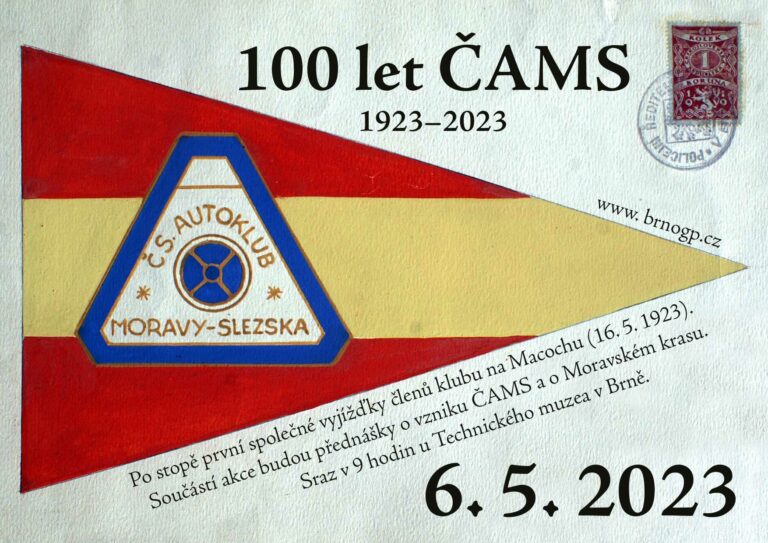

Mr. Miroslav Krejsa is a well-respected racer who has gained great respect during his active professional career by participating in countless races, for example six times in the Paris-Dakar Rally, in the Monaco Historique Grand Prix, in the Le Mans Classic, in the Spa Classic, in Prescott Hill Race, in Goodwood and many other races. He has recently gained wide recognition from the public thanks to the organization of the famous race 1000 Czechoslovak miles, which he organized for ten years and turned it into a less prestigious veteran event in the Czech Republic.

Le Mans, Spa, Monaco

Mirek Krejsa

Dalibor Janek for Motor Journal 2012/04

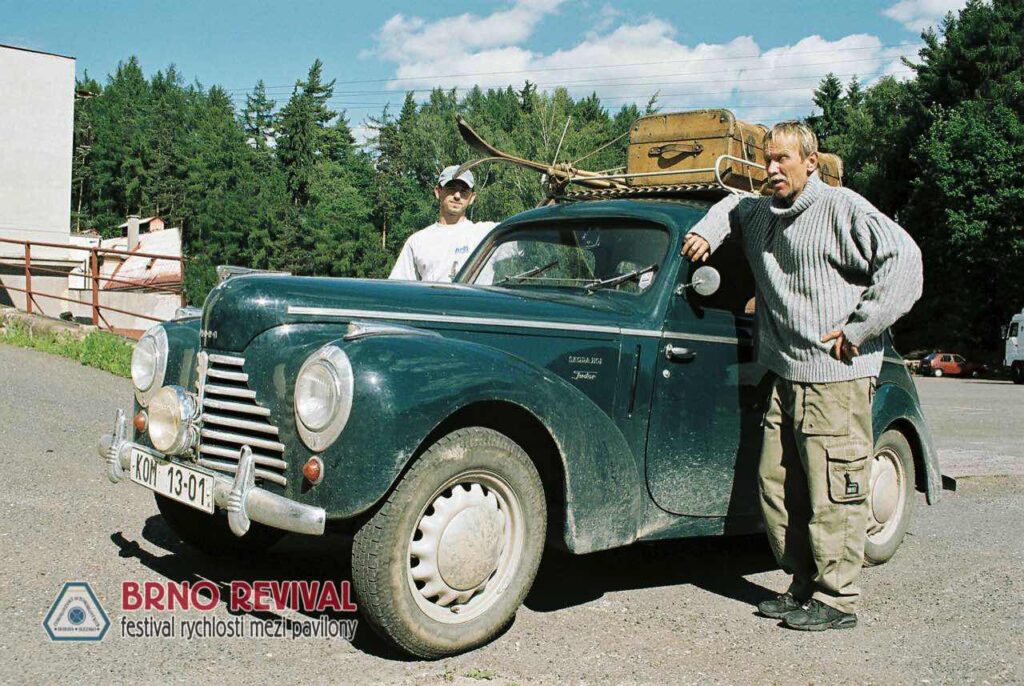

If you were driving through Jablonec nad Nisou, don't be fooled by a large advertisement for a Peugeot car dealership. It is led by Mirek Krejsa and he is our man. One hundred percent veteran. As proof, just look into his garages, which hide real treasures. And maybe, if you ask nicely, Mirek will show you some of the pieces in person, for example a 1923 Praga Alfa, a 1927 Laurin & Klement 110, a 1933 Aero 1000, a 1934 MG, a 1933 Lagonda 3L, a 1939 Popular, with whom Mirek was as far as Mauritania. And he says he has a six-seater for business trips.

Still young

"It's not that terribly expensive. I buy cars that are quite broken down, this is called pre-renovation condition professionally, and I put them together myself. Here in Jablonec, we can make a lot of things, vintage cars are expensive for people who have them repaired by specialist companies. Sometimes I get caught too. Before the Christmas holidays, there were cheap flights to England. I knew there was a lagonda for sale. I wanted to look at her. Just look. And as I looked, I had to have it. She is gorgeous. It had a broken transmission, so it was cheaper. I've already fixed the gearbox and I'll be leaving soon.'

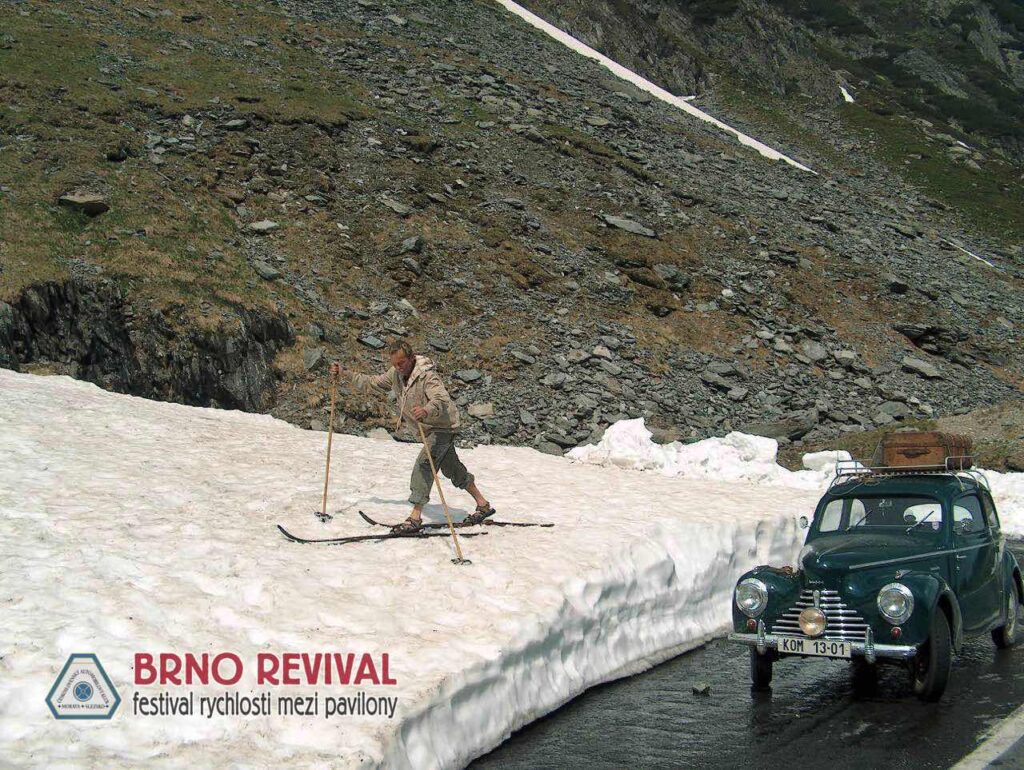

Perhaps the vast majority of owners of vintage machines mainly deal with repairing and modifying their pieces, finding the appropriate historical parts and then polishing and preserving them. From time to time, preferably in decent weather, they go out with them, either on a trip or to some kind of veterans' gathering. But nowhere Krejsa. She races like a teenager. And maybe even more. However, look at the title of the article, these are the places where Škoda racing "pancakes" from 1949 are enjoyed behind the wheel.

When he graduated from the industrial school in Jablonec, he was lucky enough to join Škodovka in Mladá Boleslav and straight to the workshop where competition cars were prepared. He couldn't do it, and he and Pepík Konečný started riding the then A-1 group. They had successfully completed three competitions, Mirek then sped up a little - probably more than a little. There were three somersaults through the roof, Mirek fell out of the car, but subsequently, despite this accident, he felt that the competition suited him. His decision was clear - they need to be continued.

Years of maturation

After two years, he left the Škoda factory and returned home to Jablonec. He joined Liaz, where he met a similar guy, who was Jirka Moskalů. He didn't think about anything else but the races either. At the time, the most suitable car for the unmodified class was the Fiat 128 coupe. Mirek bought this and often won hill races with it. And when he didn't win, Tonda Charouz won, who also started at that time and also started with a fiat. The final stop for the beautiful coupe was the uphill race held on Tuesday near Bezdružice. Mirek drove through one special stage, which, according to the instructions of the organizers, was detoured to avoid a collision between the training crews.

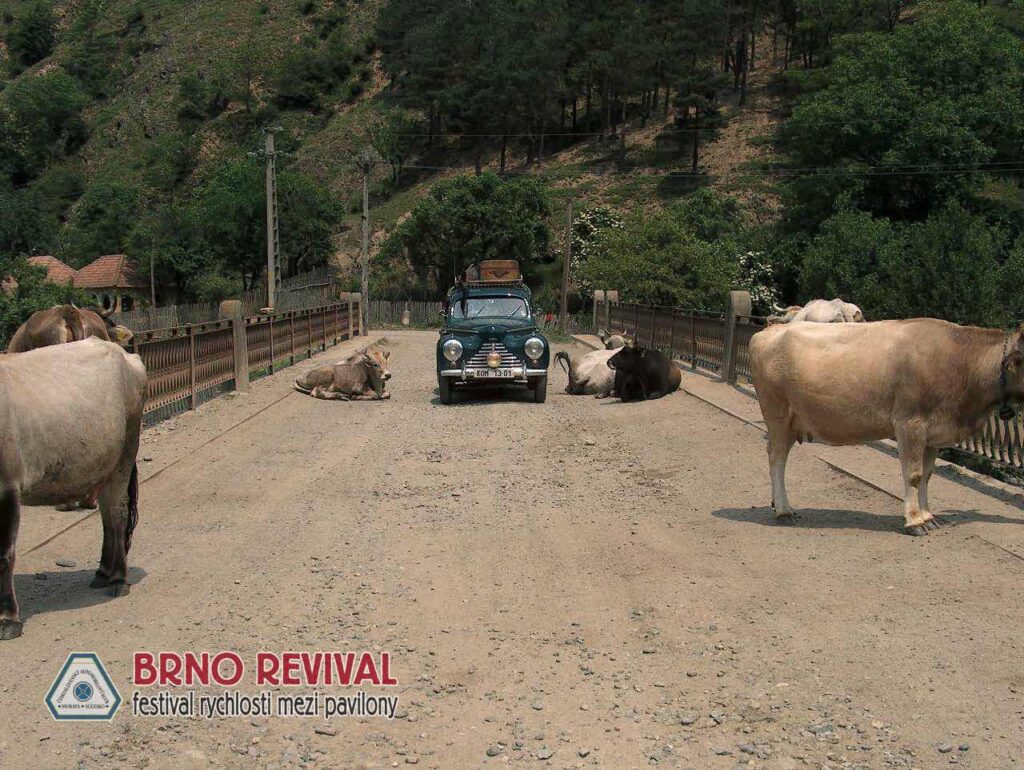

"I was young and stupid, I didn't have my seatbelt on, my helmet was in my trunk and I had a cigar in my mouth. In this state of mind, I flew onto a narrow bridge, in the opposite direction I had an eleven hundred and fifty Škoda. Her driver did not take into account the organizer's instruction and was returning in the opposite direction. I swerved to the right into the bushes, unfortunately there was an overgrown railing from the bridge, I broke through it and jumped seven meters into the forest. Nothing actually happened to me, but the fiat didn't survive. It was after the season.'

In Liaz, Mirek worked on investments and was headed by a deputy, who was a decent guy. We managed to chat up the comrade and he bought Easter after Jílek from Metalex, the so-called "zero two". Moskal had "zero three" and both formulas in the yellow-blue company color were not absent at any domestic races. Sometimes drama, that's how it sometimes happens at races. Like during a race uphill in Vysker. Krejsa was so fast in the corner that he fit under the guardrail and couldn't get out. He had to wait for the organizers to find a "windbreaker" somewhere, which raised the barrier and freed the rider. Those were good times with the formula, it wasn't a "box", but Mirek was regularly in the top ten.

Now let's skip the era of Krejs's Dakars and stay with the circuits for a while longer. Zdenek Vojtěch, a friend and famous competitor, had two sons growing up at home, and he decided that he should teach them to race. And so Vojtěch together with Igor Salaquarda and some Germans entered the Peugeot Cup. This is how Mirek Krejsa describes Vojtěch's motives. But it is possible that there were other and more important reasons. They raced with two-liter 306s and, apart from Brno and Most, they drove all over Europe.

“Zandvoort, A-1 Ring, Le Castellet, and I don't even remember where we drove. But for the first time I experienced a slightly different way of racing than I was used to. I remember that quite well. I learned from the formulas that the riders treat each other quite decently. Otherwise, they would be thrown through the air quite a bit in case of greater mutual contact. Behind the wheel of the Peugeot, I found out that pushing off the track is normal and contacts during braking do not really excite anyone. It took me about half a year to get used to it. Then I learned it and used it just like the others.'

The Dakar phenomenon

Dakar and Liaz, Liaz and Dakar. They cannot be separated from each other. The Jabloneck factory was the first Czechoslovak swallow on African routes. Of course, Krejsa was also involved in this. He recalls that he started in Dakar about four times with the Liaz, twice then he rode as an escort. Once with a private lika, which, he says, he brought to Cape Town almost on his back. Immediately in the Tenéré desert, the bearing seized, so he removed the axles and continued without front drive, only on the rear. It was said to be a challenging year, Mirek still remembers today. He had a French policeman and a German dentist as passengers, a rather atypical combination. Since then, he doesn't like the shovel either, they used to throw a lot back then.

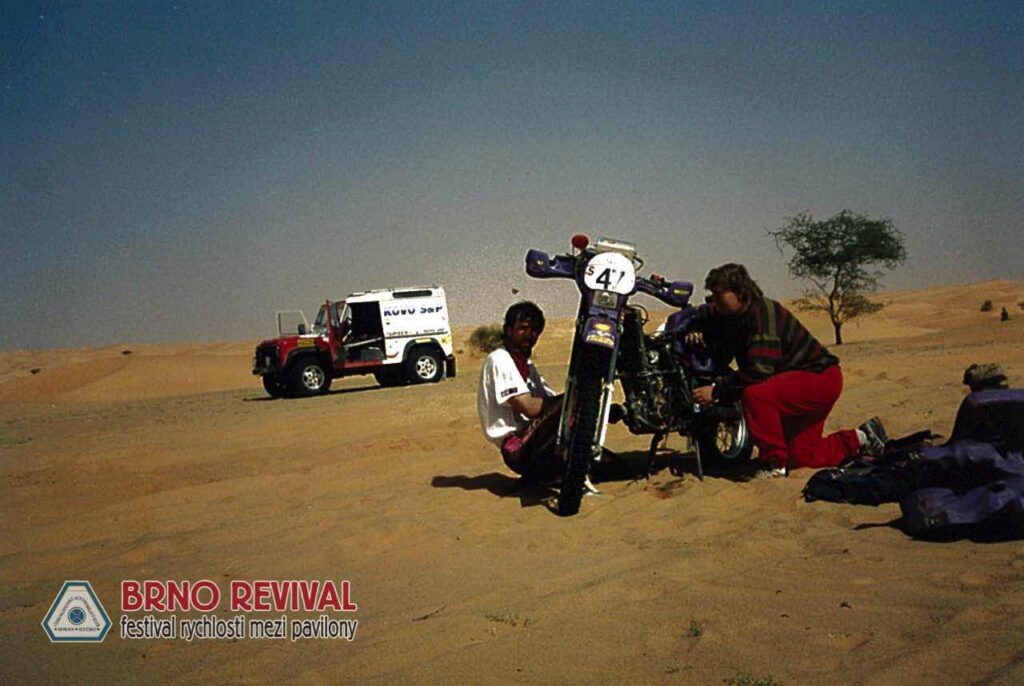

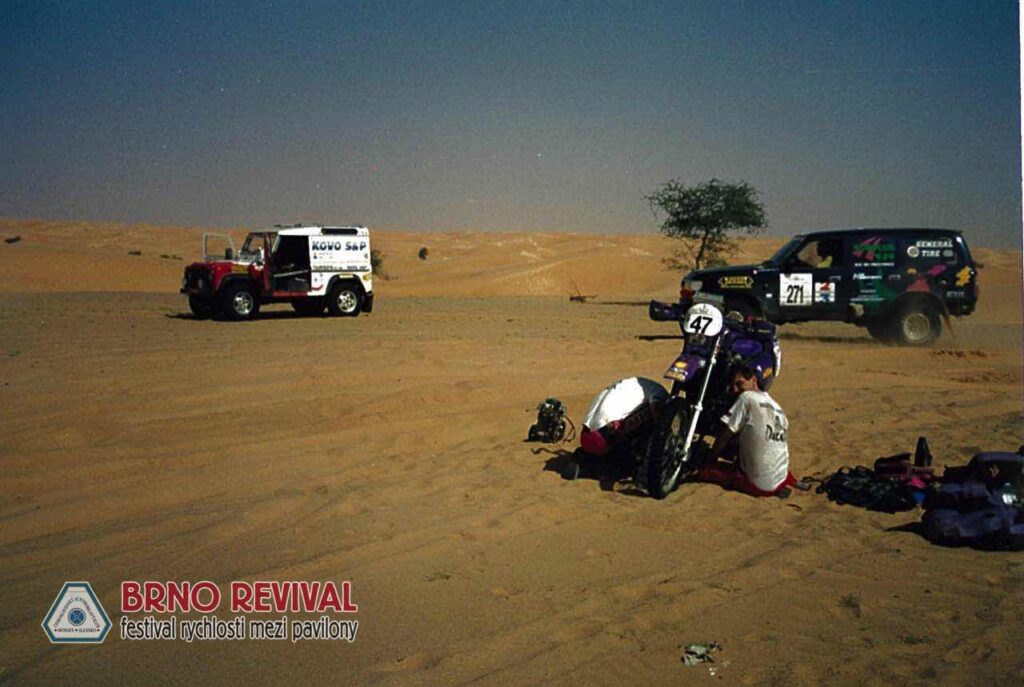

In 1993, he started as an escort with a land rover in the Kovo team, for which two Czechs started for the first time on a motorcycle - Bohouš Posledni and Libor Podmol. There were three Land Rovers, their task was to accompany the bikers. In addition, Pepík Kakrdů could try to drive to the location with one of those land rovers. He didn't succeed, they dropped out in about the third stage with some technical problem. The third Land Rover ended up on the roof.

The Land Rovers had bad shock absorbers and this caused a lot of trouble for all the crews. At the time, it was Paris–Dakar–Paris, and Mirek Krejsa and Radek Záruba managed to complete the entire competition all the way to Paris. In the category of passenger cars with diesel engines, they were classified, due to their original mission, in a very respectable 3rd place.

"We have proven ourselves quite well as an escort. God the Last's engine was damaged, it was more or less without compression. You just couldn't go with it. So we actually dragged him all the way to Paris on a rope. However, it was much more complicated. The problem occurred before the last two African stages, so we agreed on the following tactics. According to the regulations, Bohouš had to pass the finish of the stage and the start of the next stage. So he always filmed it before the goal and talked about the goal somehow. He started with the same problem and stopped after a few tens of meters. We harnessed him and God was holding the handlebars with one hand and the rope with the other. I admired him. He was also on his lips every three to four kilometers. When we were far enough away that nothing could be seen, we loaded the motorbike onto a lick that was driving nearby. Before the finish line, we removed the motorcycle from the body, I hitched it up again and pulled it to the finish line. Bohous turned the bike around and crossed the finish line. This is how we managed the two remaining African stages. From Spain to Paris there was only a connecting rod, there we loaded him on a truck. There was only one short special stage left somewhere near Granada. Somehow, Bohous started, but didn't finish it, it was already clear in advance that it wouldn't work. But nothing happened, there was only a penalty for not finishing, not exclusion from the competition. So, with our help, Bohouš reached the finish line in Paris and was the first Czechoslovak to finish the Dakar Rally. Before him, Pavel Ortů had already tried it, but he probably lay down somewhere and didn't manage to finish."

But that's not all. I once heard somewhere about some kind of engine replacement that you were saving to replace Libor Podmol?

"We were driving some desert stage and suddenly I saw a parked motorcycle on the horizon and the figure of a rider next to it. So I think - we'll go there to see if it's one of our guys. It was Mouka, as Podmol was called. He was lying on the motorcycle sunbathing, calling for help on the radio. You can't help me, the engine is completely and totally seized, he reported. So I tell him: We'll put a new one in there, I have it loaded in the back of the car. Indeed, we had a spare KTM engine wrapped in plastic. So we installed it, and in about two hours Libor stepped on the bike and drove off. The funny thing was that he had some trained specialist from KTM with him who flew for them, and only he knows how to manage it. When we arrived at the finish line in the evening, Pepík Kaliů told us that the mechanic was struggling, that we couldn't and couldn't handle it. Pepík told him that if we have a motor and at least combinations, then we can do it. That was 1993 and it was my last Dakar.”

From Kutná Hora to Le Mans

After that, Mirek had some racing peace. He was woken up by his friend Honza Egida from Kutná Hora, who, like Mirek, collects veterans. Among other valuable pieces, he also got his hands on a Skoda car with which the Škoda drivers Bobek and Netušil competed in Le Mans in 1950. They fell off after thirteen hours on the bird's nest - the locking pin fell out of the piston pin. Honza signed up for the Le Mans Classic, but somehow it didn't work out with the start. Krejsa then took over and in 2006 he started in Le Mans for the first time. He has been there three times since then.

"It's held once every two years and it's beautiful, because the cars that participated years ago start there. I also drove a Škoda in Spa, it's a wonderful circuit. I also drove the Grand Prix of Pau and Monaco. They go there a week before the EF-1s and the visits tend to be the same as at the World Cup. Amazing atmosphere. The funny thing is that the cars have to be the same as they were years ago, so no safety features at all. No arch, no belts, I just have to wear a fireproof coverall and underwear and socks. The Škoda is built on a Tudor chassis, the engine has a volume of 1150 cm3, there was also a variant with a Roots blower, or a fifteen-cylinder. The engines were different. I did everything possible with the 1100 engine, and it runs nicely. I drive up to 215 km/h on the long straight at Le Mans, please on 5.50 on 15 diagonal tires. So far nothing has fallen off the car. But if it fell, I couldn't help but laugh, because the only safety feature would be to hold on to the steering wheel.

For three starts in France, we have already gained quite a name, the first participation was particularly spicy. The factory Škoda ran a straight gear transmission, which I did not have. I used more or less the stock one instead, which didn't last. After every training session and after every race, take the gearbox out and repair it, turn two bad ones into one good one. When I arrived the next time, everyone was already calling me: Hello, Mister Gearbox! However, I already had a gearbox with straight teeth, the Hewland system, that's fine. At the last start I was able to drive out of seventy cars in fifth place. It is also due to the fact that the old men start and do not charge much for it. It's fun to start in the classic way at Le Mans. The older gentlemen are not sprinters, so last year I was second in the first corner after the start, which is known as Dunlop!'

Constant need for adrenaline

Not to mislead the reader that veterans drive 24 hours a day. Not. The race is preceded by three three-and-a-quarter-hour training sessions, according to the times achieved, the first one-hour race starts. According to the result of the first race, the second race is started, and according to the result of the second race, the third race, again an hour long, is started. Its result is the final ranking. It is therefore possible to work forward with gradual improvement, of course it is also possible the other way around. In order to compare the differences in the volume and power of the engines, the results are multiplied by the calculated coefficients. In the case of Mirek Krejsa's 1150 Škoda, the coefficient is 0.7. Another start in Le Mans is very tempting to Mirka, the brake is 4600 euros for the application. That's really a lot of money.

"It's expensive, but beautiful. In addition, Le Mans is a suitable track for Škoda, there are long straights and the brakes just need to cool down. They have to be old drums, and even if an aluminum heatsink is made over them, it's not enough. The drums expand with heat. When I drove at Spa last year, it slowed me down for about twenty minutes, then the pedal was on the floor and it was over. I have to deal with it somehow, fortunately the Škoda is light, it weighs only 615 kg, and I don't weigh eighty kilos either, so I don't stress the brakes that much. It was wet in Spa, it was my first wet ride with a pancake and it was quite fun. It was enough to lightly touch the gas and my ass was already ahead of me. I didn't have the engine on the brake, but I think it won't miss much up to 150 hp. So the car is over-revving like a pig.

Honza Egidy takes me as a doctor who teaches cars to race, I've already done quite well with Škoda in six years of work. But be careful, I have to put the clinic on full alert again, because Honza got a son-in-law from 1929, the full name is BZV. It originally had a six-cylinder two-stroke engine! So far, it has a Vauxhall six-cylinder built into it and is supercharged by a Roots blower, but Honza is said to have already discovered the original two-stroke engine block, and I'm curious about that. I drove a hill race in England with this modified car and it behaved quite funny there. He is also a thrifty Honza, so the car has old tires from a field kitchen. It's not much for racing, but you've probably noticed that I like adrenaline. And veterans.”